The intricate dance of natural selection has sculpted an astonishing array of visual systems across the animal kingdom, from the multifaceted gaze of a dragonfly to the sharp, focused lens of an eagle, leaving scientists with a profound and historically unanswerable question: What precise environmental pressures guided these vastly different evolutionary paths? For generations, the inability to rewind time and observe the ancient world has been a fundamental barrier to understanding why form follows function in the development of sight. Now, a groundbreaking computational framework developed by researchers at MIT offers a virtual window into the past, simulating evolution to reveal how an organism’s survival needs act as the primary architect of its eyes. This work not only provides a powerful tool for exploring biology’s deepest questions but also charts a new course for designing the advanced sensors of tomorrow.

From a Flys Mosaic to a Humans Focus

The natural world presents a dizzying spectrum of visual systems, each a marvel of biological engineering. A housefly sees the world through thousands of individual lenses, creating a low-resolution mosaic that is exquisitely sensitive to motion. In stark contrast, a human eye functions like a high-resolution camera, focusing light through a single lens onto a dense retina to capture fine details with exceptional clarity. This diversity poses a central evolutionary puzzle. Biologists have long theorized that these differences arose as specific adaptations to an animal’s niche—its environment, its prey, and its predators—but tracing these connections back through millennia of evolution has been largely a matter of inference and educated guesswork.

The core challenge has always been the absence of a time machine. The specific environmental pressures and behavioral tasks that shaped the eyes of ancient creatures are lost to history, making it impossible to directly test hypotheses about their evolution. Why did one lineage develop compound eyes while another perfected the camera-type eye? Was it the need to navigate a cluttered forest, spot a distant predator, or identify a specific type of food? Without the ability to run controlled experiments on evolution itself, these questions have remained at the frontier of biological science, awaiting a new method to bridge the gap between present-day anatomy and its ancient origins.

A Scientific Sandbox for Recreating Evolution

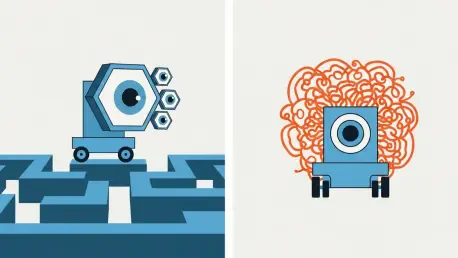

In response to this historical blindness, the MIT team developed a revolutionary computational framework, a “scientific sandbox” where the principles of evolution can be recreated and studied in a controlled digital environment. This AI-powered virtual world allows researchers to sidestep the limitations of the fossil record by simulating the entire evolutionary process from the ground up. Within this sandbox, embodied AI agents are born, learn, compete, and reproduce over thousands of generations, their visual systems adapting in response to challenges set by the scientists.

This approach represents a paradigm shift in the study of form and function. By meticulously defining the parameters of the virtual world and assigning specific survival tasks—such as navigating complex terrains or discriminating between different objects—researchers can directly observe how selective pressures guide the evolutionary trajectory of the agents’ visual apparatus. The framework essentially allows for “what-if” scenarios on an evolutionary scale, providing a dynamic platform to test long-standing theories and uncover the intricate, often non-intuitive, relationship between an organism’s purpose and its physical structure.

How an AI Learns to See from Scratch

At the heart of the simulation is a sophisticated genetic blueprint that governs the development of each AI agent. This digital “DNA” is composed of three distinct gene types. Morphological genes control physical traits, such as the placement of eyes on the agent’s body. Optical genes dictate how the eye interacts with light, including the number of photoreceptors, the properties of the lens, and the presence of structures like an iris. Finally, neural genes determine the size, structure, and learning capacity of the agent’s brain, which processes the incoming visual data. Each agent starts with a simple system, often just a single light-sensing pixel, and evolves complexity over time.

Adaptation within the sandbox unfolds along two parallel tracks that mirror natural processes. Throughout its “lifetime,” an individual agent improves through trial-and-error using reinforcement learning, receiving rewards for successfully completing its assigned task. This individual learning is then coupled with generational evolution. The most successful agents—those that perform their tasks most efficiently—are selected to pass their genes on to the next generation, with slight, random mutations introducing new variations into the pool. This dual process of learning within a lifetime and evolving across generations drives the emergence of highly specialized and optimized visual systems.

To ensure the evolved solutions are both effective and realistic, the framework incorporates crucial real-world limitations. For example, agents are given a fixed “pixel budget,” limiting the total number of photoreceptors they can develop, and their neural processing power is capped. These constraints mirror the metabolic and physical costs found in biology, such as the energy required to maintain a complex nervous system or the physical limits of optical materials. By forcing the AI to work within these boundaries, the evolutionary process is pushed toward discovering efficient, practical designs rather than computationally brute-force solutions.

Key Discoveries from the Virtual World

The experiments conducted within this virtual ecosystem yielded a wealth of data, culminating in a powerful primary conclusion: an organism’s primary survival task is the master architect of its eye. The structure of the evolved visual system was not random but was instead strongly correlated with the specific challenges the agent faced. This principle was vividly illustrated in a series of targeted simulations that produced strikingly different outcomes based on the assigned task.

Two case studies stand out. When agents were tasked with navigating complex, cluttered environments, they consistently evolved wide-field, insect-like compound eyes. These visual systems, composed of many individual optical units, provided a panoramic view optimized for detecting motion and avoiding collisions, albeit at a lower resolution. In contrast, when the survival task was changed to object discrimination—requiring agents to identify specific shapes or patterns—the evolutionary trajectory shifted dramatically. These agents overwhelmingly developed camera-type eyes with high frontal acuity, featuring structures analogous to a retina and an iris to focus on and analyze details directly in front of them, often sacrificing peripheral awareness.

Beyond confirming the task-driven nature of evolution, the research also uncovered a more nuanced insight that challenged the simple “bigger is better” assumption regarding brainpower. The simulations revealed a clear point of diminishing returns where increasing an agent’s neural capacity ceased to provide any performance benefit. This occurred when the brain’s processing power outpaced the eye’s physical ability to supply it with high-quality information. In a biological context, such an oversized brain would be a significant metabolic liability. This finding highlights the crucial co-evolution of sensory hardware and neural software, demonstrating how physical constraints fundamentally shape and limit the development of cognitive architecture.

From Biological Insights to Robotic Reality

The implications of this research extend far beyond the digital confines of the sandbox, promising to have a dual impact on both fundamental science and applied technology. For evolutionary biologists, the framework provides a powerful new methodology for testing hypotheses that were once purely theoretical. Scientists can now run countless “what-if” experiments, altering environmental variables or survival tasks to probe the potential evolutionary pathways that led to the diverse eyes seen in animals today, potentially unlocking new chapters in our understanding of life’s history.

Simultaneously, the framework serves as a practical design tool for engineers and roboticists. Instead of relying solely on human intuition to create sensors, engineers can now use this simulator to evolve them. By defining the operational goals and constraints for a robot, drone, or even a wearable medical device—such as its need to navigate a warehouse, its energy budget, and its manufacturing cost—the system can generate a novel, task-specific sensor design that is optimally balanced for its intended purpose. This approach heralds a new era of bio-inspired engineering, where solutions are not just copied from nature but are discovered through the same evolutionary principles.

The development of this evolutionary sandbox marked a significant step forward in our ability to probe the fundamental link between function and form. It provided a novel method for testing age-old biological hypotheses and offered a practical blueprint for designing the next generation of intelligent sensors. By successfully recreating the process of natural selection in a virtual environment, the research demonstrated that the most complex biological structures could be understood as elegant solutions to specific, tangible problems. This work not only answered questions about how eyes came to be but also opened up a new methodology for scientific inquiry, one where simulation and AI could be used to explore the deepest mysteries of the natural world and inspire the innovations of the future.