The seemingly limitless potential of artificial intelligence is tethered to a very terrestrial problem: an insatiable and rapidly growing appetite for energy that strains our planet’s resources. As AI models become more complex and their applications more widespread, the data centers that power them consume vast amounts of electricity and water, contributing significantly to global carbon emissions. To sever this connection between technological progress and environmental degradation, a team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania has unveiled a groundbreaking design for orbital data centers. This innovative concept proposes moving the computational heart of AI into Earth’s orbit, creating a highly scalable infrastructure powered entirely by the sun. Detailed in a paper presented at the 2026 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics SciTech Forum, this vision leverages established space technology to offer a plausible and sustainable path forward for the future of artificial intelligence, mitigating its environmental footprint by tapping into the clean, inexhaustible resources of space.

A Radically New Architecture in Space

At the core of this ambitious proposal is a tether-based architecture that cleverly uses the laws of physics to achieve stability and orientation without complex propulsion systems. The design centers on a long, high-strength, flexible cable placed in orbit around the Earth. On this tether, the planet’s gravitational pull is slightly stronger on its lower end, while the centrifugal force generated by its orbital velocity is stronger on its upper end. This constant interplay of forces, a phenomenon known as gravity-gradient stabilization, naturally pulls the tether taut and aligns it in a consistent vertical orientation relative to the Earth’s surface. By harnessing these passive forces, the system entirely avoids the need for fuel, thrusters, and the associated weight and complexity required for active station-keeping. This elegant solution not only simplifies the design but also significantly enhances its operational longevity, making it a robust and reliable foundation for a massive computational network in space.

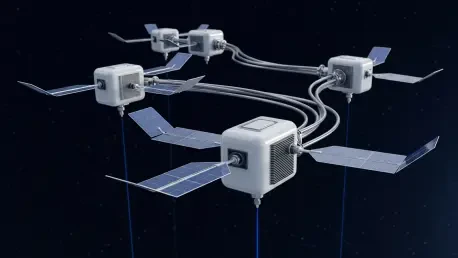

This stable tether serves as the structural backbone for a remarkably modular and scalable data center. Rather than launching a single, massive, and rigid structure, the system is envisioned as a long, distributed chain composed of thousands of individual computing nodes. These nodes, each a self-contained unit housing computer chips, dedicated cooling hardware, and branching solar panels, would be attached along the length of the tether. Associate Professor Igor Bargatin, the project’s lead, likens the expansion process to “adding beads to form a longer necklace,” highlighting the design’s inherent flexibility. This modularity means the data center’s computing capacity can be incrementally increased over time by simply adding more nodes. A single tethered system could eventually stretch for tens of kilometers, hosting thousands of these units and creating a colossal, yet gracefully simple, computing infrastructure that grows in tandem with the demands of global AI workloads.

Harnessing the Sun for Power and Control

One of the most innovative aspects of the design is its dual use of sunlight as both a power source and a key component of its control system. Each computing node is equipped with branching, leaf-like solar panels specifically engineered to be self-orienting. This is achieved by leveraging solar radiation pressure—the gentle but persistent force exerted by photons as they strike a surface. By carefully designing the panels with lightweight, thin-film materials and angling them slightly in relation to the main hardware, this pressure acts much like wind on a weather vane. It passively and continuously rotates the panels to keep them pointed directly at the sun, ensuring maximum energy collection at all times. This passive control mechanism is a significant departure from traditional satellite designs, which rely on heavy, power-hungry, and failure-prone systems of motors, sensors, and thrusters to maintain orientation. This approach drastically reduces the system’s overall weight, complexity, and internal power consumption, making it more efficient and reliable.

Through extensive computer simulations, the research team demonstrated that a single tethered system could support up to 20 megawatts of computing power, a capacity that is directly comparable to a medium-sized data center on the ground. This substantial power budget would be more than sufficient to handle intensive AI workloads. To manage the vast flow of information generated and processed in orbit, the system would transmit data to and from Earth using laser-based optical communication links. This technology, which uses focused beams of light to carry data, is an existing and proven method for achieving high-bandwidth, high-speed communication between satellites and ground stations. By integrating this established communication technology, the orbital data center could seamlessly connect to global networks, providing the low-latency responsiveness required for a wide range of AI applications while being powered entirely by clean, renewable solar energy.

A Practical and Strategic Application

The design proposed by the University of Pennsylvania researchers strategically occupies a feasible “middle ground” between competing concepts for space-based computing. On one end of the spectrum, proposals for massive, robotically assembled rigid structures in orbit are currently beyond our deployment capabilities and present immense logistical challenges. On the other end, constellations composed of millions of individual satellites, while more technologically accessible, create significant issues related to space debris, launch logistics, and network management. The tether-based model, in contrast, is ambitious enough to be impactful yet is fundamentally grounded in existing and well-understood technologies. Space tethers have been studied, developed, and tested in orbit for decades, lending a high degree of confidence and credibility to the structural principles that underpin this novel data center architecture. This pragmatic approach significantly lowers the barrier to entry and increases the likelihood of near-term viability.

Furthermore, the team strategically focused the application of their orbital data center on AI inference rather than AI training. The process of training a large AI model requires transmitting massive datasets, and the inherent time delay, or latency, in sending this information to and from orbit would likely render the training process impractical and inefficient. However, the vast majority of future energy consumption related to artificial intelligence is projected to come from AI inference—the process where a pre-trained model is used to make predictions or respond to queries, such as those sent to services like ChatGPT. This tethered data center is perfectly suited for handling this less latency-sensitive but highly repetitive task. This focused application represents a viable path to offload a significant and growing portion of AI’s future energy demand from Earth’s terrestrial power grids, directly addressing one of the most pressing sustainability challenges in modern technology.

Built to Survive in a Harsh Environment

A critical aspect of the research involved a thorough assessment of the structure’s durability against the constant and unavoidable threat of micrometeoroid impacts in low Earth orbit. Any large-scale structure in space must be designed to withstand a continuous barrage of tiny, high-velocity particles. Associate Professor Jordan Raney and doctoral student Dengge “Grace” Jin conducted extensive simulations to model the cumulative effect of numerous small impacts across the entire lengthy structure. Their findings revealed a high degree of natural resilience inherent in the flexible, tether-based design. Instead of a catastrophic failure, which might occur with a rigid structure, an impact on the tether would induce a transient wobble or vibration. This wave of energy would propagate along the flexible cable and naturally dissipate over time, a dynamic Raney compares to the gentle ringing of a “wind chime.”

The simulations demonstrated that even when subjected to a relentless storm of micrometeoroid impacts, the system would deviate from its optimal vertical orientation by only a few degrees, well within acceptable operational tolerances. This inherent resilience is further enhanced by a thoughtful implementation of structural redundancy. Each individual computing node is designed to be supported by multiple tethers, creating a robust, web-like support system. This ensures that the overall structure can maintain its integrity and functionality even if a single tether is severed by a larger-than-expected impact. This combination of flexibility and redundancy provides a powerful defense against the hazards of the space environment, ensuring the long-term viability and operational stability of the orbital data center without the need for active repair missions or overly complex shielding systems.

The Path Forward from Simulation to Reality

While the comprehensive design presented a compelling and viable vision for sustainable AI, the researchers acknowledged that significant engineering hurdles had yet to be overcome. The primary challenge identified was thermal management. On Earth, data centers rely on air and water to carry away the immense waste heat generated by computer chips. In the vacuum of space, however, systems can only cool themselves by radiating heat away, a much slower and less efficient process. The initial design incorporated radiators, but the team determined that further development was needed to create lightweight, highly efficient, and durable radiator systems capable of dissipating the intense thermal loads produced by sustained, high-performance computing. This became the central focus of their subsequent engineering efforts. With a clear roadmap, the team’s immediate next step was to transition from computer simulations to physical experimentation. They initiated plans to build and test a small-scale prototype with a limited number of nodes, a critical move that allowed them to validate their models and refine the design. This practical step brought the world closer to a future where, as Bargatin had envisioned, a “belt of these systems” could one day encircle the planet, providing the continuous, clean power needed to sustain the world’s ever-growing AI infrastructure.