The rapid adoption of artificial intelligence-driven well-being technologies throughout the corporate world has quietly ushered in a significant ethical dilemma, creating a gap where employee autonomy is increasingly at risk. While these sophisticated tools promise to support mental health, mitigate burnout, and foster a healthier work environment, they are built upon a foundation of consent that is fundamentally broken and ill-equipped for the modern workplace. The traditional “informed consent” checkbox, a relic of a simpler digital age, is proving to be a woefully inadequate safeguard against the complexities of continuous AI data collection and the persistent, inherent power imbalances that define the employer-employee relationship. This outdated and superficial approach fails to protect worker privacy and dignity, necessitating a complete reevaluation and the urgent development of a more robust, affirmative, and structurally supported model for what it means to truly consent.

The Collapse of Traditional Consent in the Modern Workplace

The Scope and Nature of the Problem

The corporate wellness market has undergone a dramatic transformation, expanding into a formidable industry valued at over $53.5 billion in 2024, with AI-powered tools decisively leading this expansion. Advanced technologies such as mental health chatbots like Woebot and Wysa, alongside stress-tracking platforms like Virtuosis AI that analyze vocal patterns for signs of strain, are no longer considered peripheral benefits or niche perks. Instead, they are being woven deeply into the very fabric of core employment systems and infrastructure. A prime example of this integration is the partnership between major healthcare and financial firms to embed health analytics directly within payroll systems. This profound shift signifies the normalization of constant, algorithm-driven monitoring under the benevolent guise of promoting well-being, turning the systematic collection of deeply personal data into a routine and expected part of employment for millions of workers globally, often without their full comprehension of the long-term implications for their careers and personal lives.

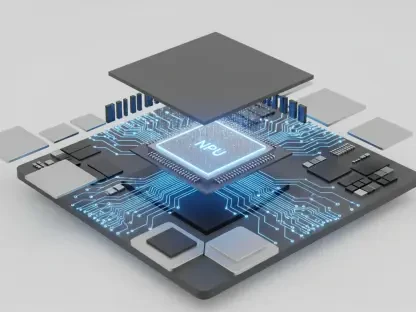

At the heart of this ethical quandary lies a fundamental and irreconcilable mismatch: traditional models of consent are designed as static, one-time events, whereas the AI well-being systems they govern operate on a principle of continuous, unending data collection. An employee’s initial click of an “agree” button cannot realistically or ethically encompass the perpetual and evolving nature of the data gathering that will follow throughout their tenure. This initial consent is rendered functionally meaningless almost immediately, as it fails to account for the ongoing surveillance and the array of highly sensitive and personal inferences the AI will generate about an individual’s mood, stress levels, and potential for burnout. The initial “yes” becomes a permanent, unalterable decision that does not accommodate changes in an employee’s comfort level, the technology’s capabilities, or how the data might be used in the future, creating a significant and persistent ethical vulnerability that leaves workers exposed.

The Human Factor Power and Psychology

The integrity of meaningful consent is further compromised by the deliberately vague, complex, and often obfuscated language used in privacy notices and terms of service agreements. Corporations frequently rely on opaque corporate jargon, using terms such as “aggregated,” “anonymized,” or “used to improve engagement” to obscure the granular reality of how an individual’s sensitive personal data is being collected, analyzed, and leveraged. This linguistic smokescreen makes it nearly impossible for a non-expert to grasp the full scope of the surveillance to which they are agreeing. This problem is significantly compounded by the pervasive psychological phenomenon known as “consent fatigue.” In a digital work environment saturated with constant requests for agreement—from cookie banners to software updates—employees become conditioned to reflexively click “yes” simply to dismiss the notification and continue with their tasks. This behavioral conditioning strips the act of giving consent of its ethical weight, reducing a critical decision about personal autonomy to a thoughtless, automated chore rather than a considered and deliberate choice.

Ultimately, no consent form, no matter how meticulously worded, can be truly effective in a professional environment characterized by such a stark and inherent power imbalance. Consider the common scenario where a manager suggests an “optional” wellness tool to a subordinate; for the employee, declining this offer is rarely a neutral act. It can feel fraught with professional risk, potentially impacting performance reviews, opportunities for promotion, or the overall relationship with management. In this context, consent ceases to be a genuine expression of free will and instead becomes a performance of compliance, a “tacit obligation” driven by a pragmatic need for professional self-preservation. This dynamic effectively transforms the offer of a supportive tool into a coercive mandate. The public criticism faced by major corporations for their wellness-framed monitoring systems serves as a potent real-world example of how the positive rhetoric of well-being can be co-opted to justify increased surveillance and intensify productivity pressures, proving that genuine consent cannot exist without first fundamentally addressing and mitigating the underlying power structures of the workplace.

Forging a New Path Affirmative Consent and Structural Change

Introducing a Robust Ethical Framework

To adequately address this profound ethical void, it is essential to adopt a new, more rigorous framework for consent, one that is drawn from the nuanced and well-developed principles of affirmative consent theories. The FRIES model, an acronym that stands for Freely Given, Reversible, Informed, Enthusiastic, and Specific, offers a much higher and more appropriate standard for what should constitute meaningful agreement in the workplace. This model fundamentally shifts the ethical baseline away from the passive, outdated standard of “no means no”—which merely requires the absence of an explicit refusal—to the active, empowering principle of “yes means yes.” This new standard demands a clear, unambiguous, and willing expression of ongoing agreement from the employee. By establishing such a high bar, the FRIES framework moves beyond the superficiality of a checkbox and requires organizations to demonstrate that consent is an active, conscious, and continuous process, thereby recentering the conversation on the employee’s autonomy and right to control their own data.

Applying the specific tenets of the FRIES model to the typical corporate environment starkly illuminates the deep-seated inadequacies of current data collection practices. Consent is not Freely Given when an employee fears professional repercussions or penalties for declining to participate. It is not Reversible if the act of opting out at a later time invites suspicion, scrutiny, or negative attention from management. It can hardly be considered Informed when the inner workings of the AI algorithms remain opaque black boxes and the full extent of data usage is obscured by technical jargon. Furthermore, consent is rarely Enthusiastic when it is given out of a sense of obligation or to avoid being perceived as uncooperative. Finally, it fails the test of being Specific when a single, all-encompassing agreement authorizes broad, undefined, and potentially limitless data collection for a variety of unspecified purposes. This detailed framework provides more than just a theoretical ideal; it serves as a practical and actionable checklist for organizations to build more ethical, transparent, and respectful systems for employee well-being.

Beyond Technology The Imperative for Cultural Reform

Resolving this complex issue demanded more than just designing better technology or drafting clearer privacy policies; it called for a comprehensive socio-technical solution deeply rooted in organizational and cultural change. Experience showed that true, meaningful consent could only become possible within a workplace environment built on a foundation of genuine trust, mutual respect, and psychological safety. Forward-thinking employers moved to guarantee that participation in any well-being program was genuinely voluntary, establishing a clearly protected and penalty-free right for employees to opt out at any time without fear of reprisal. To ensure accountability, data practices were made fully transparent and subjected to regular, independent audits. Most critically, these organizations recognized the necessity of addressing the root causes of employee burnout—such as excessive workloads, poor management practices, and toxic work environments—rather than deploying AI as a superficial, algorithmic bandage. The guiding principle became that the ultimate goal was not to build a sophisticated AI that could merely simulate care, but to cultivate a workplace where care was already a core, demonstrated value and where employee autonomy was fundamentally respected.