The very artificial intelligence systems designed to enhance critical decision-making in fields like medicine could be systematically failing the exact populations they are intended to serve. This unsettling paradox exposes a fundamental flaw in how we measure AI performance, where a model celebrated for its high overall accuracy in a controlled environment can become dangerously unreliable when deployed in the real world. This discovery challenges the core assumptions guiding AI development and forces a critical reevaluation of what it means for a model to be truly effective and trustworthy.

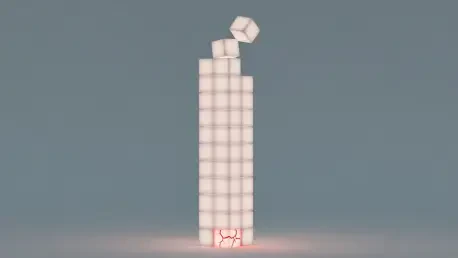

The issue stems from a deep-seated reliance on top-line performance metrics. An AI that is 95% accurate sounds impressive, but that simple number can mask catastrophic failures for the remaining 5%. When applied to diverse populations or new operational settings, these hidden weaknesses can become magnified, leading to significant consequences in high-stakes applications. The disconnect between laboratory success and real-world utility represents a growing crisis of confidence, demanding a shift toward more robust and granular evaluation methods to ensure AI systems are safe, equitable, and reliable for everyone.

When a Top Performer Is Just a Title

What if the model that consistently tops the leaderboards is the one making the most critical errors in practice? This is not a hypothetical scenario but a documented reality. The highest-achieving AI in a development setting can, upon encountering a new environment, produce the worst outcomes for significant portions of the population. This phenomenon reveals that a “top performer” title, earned based on average scores, offers a false sense of security.

The core of this paradox lies in the transition from a known to an unknown environment. A model’s stellar performance during training can mask its inability to generalize its knowledge correctly. It may have learned shortcuts or irrelevant patterns specific to its training data that do not hold true in a new context. Consequently, when faced with slightly different data distributions—such as patient demographics from a different hospital—its performance can degrade unpredictably, failing the very subgroups it was designed to help.

The Hidden Crisis in AI Evaluation

The widespread practice of judging an AI model’s success based on high-level, aggregate statistics like overall accuracy is at the heart of the problem. These single-number summaries are convenient but dangerously incomplete, obscuring critical failures that occur within specific slices of data. In fields like medical diagnostics, a model might be highly accurate on average but consistently misdiagnose a rare condition in a particular demographic. Similarly, an AI designed for hate speech detection could perform well overall but fail to identify nuanced, culturally specific forms of harmful content.

As artificial intelligence is integrated into increasingly diverse and dynamic environments, this reliance on simplistic metrics becomes untenable. The hidden failures buried within these aggregate scores can have severe real-world consequences, from incorrect medical treatments to the unchecked spread of disinformation. This situation highlights an urgent need to reform evaluation protocols, moving beyond broad performance measures to a more rigorous, fine-grained analysis that reflects the complexity of the world in which these systems operate.

Deconstructing the Failure of High-Performing Models

A common but flawed assumption in machine learning is the “accuracy-on-the-line” principle, which suggests that the performance ranking of models remains consistent across different datasets. In other words, the best model in one setting is expected to be the best in another. However, groundbreaking research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) directly challenges this notion, providing firm evidence that this principle is frequently broken in practice. The top-ranked model in a controlled test can easily become the worst performer when deployed on a new population.

These failures are often rooted in spurious correlations, where a model learns to associate outcomes with irrelevant features. For instance, an AI might learn to classify an animal as an orca not by its anatomical features but because it has only seen orcas against an ocean background. If it then encounters a cow on a beach, it may misclassify it as an orca, having latched onto the scenery as the decisive factor. Critically, simply expanding the dataset does not eliminate these dangerous, coincidental associations; it may even reinforce them if the biases are present in the larger dataset as well.

In real-world applications, these mistakes are more subtle but far more consequential. A diagnostic model trained on X-rays from one hospital might learn to associate pneumonia with a non-medical artifact, like a specific watermark used by that facility’s equipment. When deployed at a second hospital without that watermark, it fails to make a correct diagnosis, even though its overall accuracy remains high due to its success on other cases. This can also lead to discriminatory outcomes; a model that learns from data where pneumonia is more common in older patients might become less likely to diagnose it in younger individuals, relying on age as a shortcut instead of analyzing the patient’s actual anatomy.

A Look Inside the Groundbreaking MIT Findings

The core research exposing this vulnerability was conducted by a team at MIT, led by Professor Marzyeh Ghassemi and Olawale Salaudeen, and presented at the prestigious Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) conference. Their work moved beyond theoretical concerns to provide concrete data on the scale of the problem. They demonstrated that a model with the best average performance could become the worst-performing model for anywhere from 6% to an astonishing 75% of a new population.

This striking statistic underscores how dramatically a model’s reliability can shift when it leaves the lab. Previous findings from the same research group had already hinted at this issue, showing that efforts to improve a model’s overall diagnostic performance could paradoxically degrade its accuracy for patients with specific conditions, such as pleural effusions. These collective findings paint a clear picture: our current evaluation standards are not just imperfect; they are actively creating a false sense of confidence in systems that may be deeply flawed.

Forging a New Playbook for Trustworthy AI

The solution requires a fundamental shift in how AI systems are validated. Organizations must move beyond a dependence on aggregate statistics and adopt more rigorous, granular testing protocols that are designed to uncover hidden vulnerabilities before a model is deployed. This involves stress-testing models on diverse subgroups and out-of-distribution data to proactively identify where and why they might fail.

To facilitate this deeper level of scrutiny, the MIT research team developed an algorithm called OODSelect. This tool is designed to systematically find instances where top-performing models fail on subgroups in new settings, effectively pinpointing where the “accuracy-on-the-line” principle breaks down. By isolating these vulnerable subpopulations, OODSelect provides developers with a clear map of their model’s weaknesses, enabling them to address the issues directly.

Ultimately, these insights create a pathway toward building more robust and reliable AI. Once granular testing has identified underperforming subgroups, that information can be used to retrain or fine-tune the models. This iterative process of finding and fixing hidden failures is essential for creating systems that are not only accurate on average but also equitable and dependable across the full spectrum of scenarios they will encounter in the real world.

The research presented a stark warning about the limitations of conventional AI evaluation. The prevailing reliance on aggregate performance metrics was shown to be an inadequate and often misleading measure of a model’s true reliability. By revealing how top-performing models could fail catastrophically on specific subpopulations, the work underscored the urgent need for a paradigm shift. The development of tools like OODSelect provided a practical path forward, offering a systematic way to identify and correct these hidden flaws. This transition toward more granular and adversarial testing represented a crucial step in building AI systems that were not just technically proficient but genuinely trustworthy and equitable for deployment in society.Fixed version:

The very artificial intelligence systems designed to enhance critical decision-making in fields like medicine could be systematically failing the exact populations they are intended to serve. This unsettling paradox exposes a fundamental flaw in how we measure AI performance, where a model celebrated for its high overall accuracy in a controlled environment can become dangerously unreliable when deployed in the real world. This discovery challenges the core assumptions guiding AI development and forces a critical reevaluation of what it means for a model to be truly effective and trustworthy.

The issue stems from a deep-seated reliance on top-line performance metrics. An AI that is 95% accurate sounds impressive, but that simple number can mask catastrophic failures for the remaining 5%. When applied to diverse populations or new operational settings, these hidden weaknesses can become magnified, leading to significant consequences in high-stakes applications. The disconnect between laboratory success and real-world utility represents a growing crisis of confidence, demanding a shift toward more robust and granular evaluation methods to ensure AI systems are safe, equitable, and reliable for everyone.

When a Top Performer Is Just a Title

What if the model that consistently tops the leaderboards is the one making the most critical errors in practice? This is not a hypothetical scenario but a documented reality. The highest-achieving AI in a development setting can, upon encountering a new environment, produce the worst outcomes for significant portions of the population. This phenomenon reveals that a “top performer” title, earned based on average scores, offers a false sense of security.

The core of this paradox lies in the transition from a known to an unknown environment. A model’s stellar performance during training can mask its inability to generalize its knowledge correctly. It may have learned shortcuts or irrelevant patterns specific to its training data that do not hold true in a new context. Consequently, when faced with slightly different data distributions—such as patient demographics from a different hospital—its performance can degrade unpredictably, failing the very subgroups it was designed to help.

The Hidden Crisis in AI Evaluation

The widespread practice of judging an AI model’s success based on high-level, aggregate statistics like overall accuracy is at the heart of the problem. These single-number summaries are convenient but dangerously incomplete, obscuring critical failures that occur within specific slices of data. In fields like medical diagnostics, a model might be highly accurate on average but consistently misdiagnose a rare condition in a particular demographic. Similarly, an AI designed for hate speech detection could perform well overall but fail to identify nuanced, culturally specific forms of harmful content.

As artificial intelligence is integrated into increasingly diverse and dynamic environments, this reliance on simplistic metrics becomes untenable. The hidden failures buried within these aggregate scores can have severe real-world consequences, from incorrect medical treatments to the unchecked spread of disinformation. This situation highlights an urgent need to reform evaluation protocols, moving beyond broad performance measures to a more rigorous, fine-grained analysis that reflects the complexity of the world in which these systems operate.

Deconstructing the Failure of High-Performing Models

A common but flawed assumption in machine learning is the “accuracy-on-the-line” principle, which suggests that the performance ranking of models remains consistent across different datasets. In other words, the best model in one setting is expected to be the best in another. However, groundbreaking research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) directly challenges this notion, providing firm evidence that this principle is frequently broken in practice. The top-ranked model in a controlled test can easily become the worst performer when deployed on a new population.

These failures are often rooted in spurious correlations, where a model learns to associate outcomes with irrelevant features. For instance, an AI might learn to classify an animal as an orca not by its anatomical features but because it has only seen orcas against an ocean background. If it then encounters a cow on a beach, it may misclassify it as an orca, having latched onto the scenery as the decisive factor. Critically, simply expanding the dataset does not eliminate these dangerous, coincidental associations; it may even reinforce them if the biases are present in the larger dataset as well.

In real-world applications, these mistakes are more subtle but far more consequential. A diagnostic model trained on X-rays from one hospital might learn to associate pneumonia with a non-medical artifact, like a specific watermark used by that facility’s equipment. When deployed at a second hospital without that watermark, it fails to make a correct diagnosis, even though its overall accuracy remains high due to its success on other cases. This can also lead to discriminatory outcomes; a model that learns from data where pneumonia is more common in older patients might become less likely to diagnose it in younger individuals, relying on age as a shortcut instead of analyzing the patient’s actual anatomy.

A Look Inside the Groundbreaking MIT Findings

The core research exposing this vulnerability was conducted by a team at MIT, led by Professor Marzyeh Ghassemi and Olawale Salaudeen, and presented at the prestigious Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) conference. Their work moved beyond theoretical concerns to provide concrete data on the scale of the problem. They demonstrated that a model with the best average performance could become the worst-performing model for anywhere from 6% to an astonishing 75% of a new population.

This striking statistic underscores how dramatically a model’s reliability can shift when it leaves the lab. Previous findings from the same research group had already hinted at this issue, showing that efforts to improve a model’s overall diagnostic performance could paradoxically degrade its accuracy for patients with specific conditions, such as pleural effusions. These collective findings paint a clear picture: our current evaluation standards are not just imperfect; they are actively creating a false sense of confidence in systems that may be deeply flawed.

Forging a New Playbook for Trustworthy AI

The solution requires a fundamental shift in how AI systems are validated. Organizations must move beyond a dependence on aggregate statistics and adopt more rigorous, granular testing protocols that are designed to uncover hidden vulnerabilities before a model is deployed. This involves stress-testing models on diverse subgroups and out-of-distribution data to proactively identify where and why they might fail.

To facilitate this deeper level of scrutiny, the MIT research team developed an algorithm called OODSelect. This tool is designed to systematically find instances where top-performing models fail on subgroups in new settings, effectively pinpointing where the “accuracy-on-the-line” principle breaks down. By isolating these vulnerable subpopulations, OODSelect provides developers with a clear map of their model’s weaknesses, enabling them to address the issues directly.

Ultimately, these insights create a pathway toward building more robust and reliable AI. Once granular testing has identified underperforming subgroups, that information can be used to retrain or fine-tune the models. This iterative process of finding and fixing hidden failures is essential for creating systems that are not only accurate on average but also equitable and dependable across the full spectrum of scenarios they will encounter in the real world.

The research presented a stark warning about the limitations of conventional AI evaluation. The prevailing reliance on aggregate performance metrics was shown to be an inadequate and often misleading measure of a model’s true reliability. By revealing how top-performing models could fail catastrophically on specific subpopulations, the work underscored the urgent need for a paradigm shift. The development of tools like OODSelect provided a practical path forward, offering a systematic way to identify and correct these hidden flaws. This transition toward more granular and adversarial testing represented a crucial step in building AI systems that were not just technically proficient but genuinely trustworthy and equitable for deployment in society.