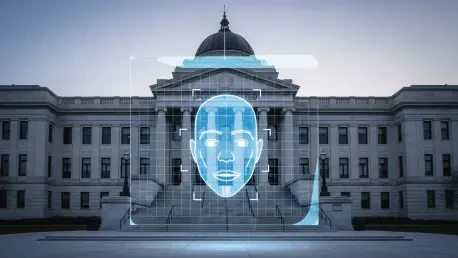

A contentious legal battle has erupted between the state of Illinois and federal immigration agencies, casting a harsh spotlight on the use of advanced facial recognition technology on the public, particularly minors. At the center of this dispute is a federal tool known as “Mobile Fortify,” which state officials and privacy advocates argue is being deployed in a manner that brazenly violates state privacy laws and fundamental civil liberties. The lawsuit, filed jointly by the state and the city of Chicago, accuses the Department of Homeland Security of creating a vast surveillance network that operates outside the bounds of established legal protections. This confrontation escalates a long-simmering national debate over the balance between federal law enforcement powers and the individual’s right to privacy in an age of increasingly sophisticated and pervasive surveillance technology, questioning whether state-level safeguards can withstand federal overreach.

An Incident Ignites a Legal Firestorm

The legal challenge gained significant momentum following a widely circulated video from October 10, 2025, which captured a troubling interaction outside East Aurora High School. In the footage, U.S. Border Patrol agents are seen approaching a group of teenagers and using a cellphone to conduct what appears to be a facial scan on one of the minors, all without any discernible consent from the youth or a legal guardian. This single event served as a powerful catalyst, transforming abstract concerns about surveillance into a tangible and alarming reality for the community. The incident immediately drew the ire of local leaders, including State Representative Barbara Hernandez, who publicly condemned the act of collecting a minor’s biometric data without permission as a profound overstep of federal authority. The video quickly became a cornerstone of the state’s case, providing a clear and disturbing example of the very practices Illinois law seeks to prevent and putting a human face on the complex legal and ethical questions surrounding biometric data collection.

The fallout from the East Aurora High School incident was swift and decisive, escalating from local outrage to a full-blown state-led lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and its subsidiary agencies, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP). What might have otherwise been dismissed as an isolated event was framed by Illinois officials as evidence of a systemic and unlawful pattern of behavior by federal agents operating within the state. The lawsuit contends that this incident is not an anomaly but rather indicative of a broader strategy to use the “Mobile Fortify” application to indiscriminately scan and collect biometric information from residents. By leveraging the video as a central piece of evidence, the state aims to demonstrate a clear violation of its residents’ rights, arguing that the federal government is knowingly disregarding state law and creating a climate of fear and mistrust, particularly within immigrant communities where such enforcement actions are most acutely felt.

A Clash Over Privacy and Precedent

At the heart of the lawsuit is the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA), a landmark piece of state legislation designed to give residents control over their unique biological identifiers, such as fingerprints and facial geometry. The state’s legal filing argues that federal agents are systematically violating BIPA’s core tenets by scanning individuals’ faces without obtaining prior informed consent and without providing a clear policy on data destruction. According to the complaint, the sensitive biometric data collected through “Mobile Fortify” is being retained for up to fifteen years, a practice that directly contradicts the spirit of the law. Illinois attorneys contend that this long-term data storage effectively creates the “general information bank” that BIPA was specifically enacted to prevent, allowing the government to monitor its residents without the checks and balances of individualized suspicion or a judicial warrant. The case represents a critical test of a state’s ability to enforce its own privacy protections against the expansive surveillance capabilities of the federal government.

The legal and ethical objections to “Mobile Fortify” extend beyond its alleged violation of state law, with civil rights experts raising serious alarms about the technology’s inherent flaws and potential for misuse. Nathan Freed Wessler, an attorney with the ACLU, has described the facial recognition tool as unreliable and “glitchy,” emphasizing the grave danger posed by its inaccuracies. A misidentification by the system could lead to devastating consequences, including the wrongful detention and potential deportation of individuals, including U.S. citizens who are mistakenly flagged. Wessler argues for the urgent implementation of stronger legal guardrails to govern such powerful surveillance tools, drawing parallels to the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Carpenter v. United States, which limited warrantless government access to cellphone location data. This precedent, advocates argue, should be extended to protect biometric information, treating it with the same level of constitutional protection as other forms of sensitive personal data. The Department of Homeland Security has so far declined to comment on the pending litigation.

The Future of Surveillance and State Rights

The lawsuit initiated by Illinois against federal agencies marked a pivotal moment in the ongoing national conversation about the intersection of technology, privacy, and government authority. The legal arguments presented in the case not only challenged the specific use of the “Mobile Fortify” application but also raised fundamental questions about the sovereignty of state laws in the face of federal enforcement priorities. The outcome of this legal battle was seen as a potential bellwether, poised to influence how other states with similar biometric privacy laws might confront federal surveillance activities within their borders. It forced a critical examination of whether existing legal frameworks, drafted in a pre-digital era, were adequate to protect citizens from the reach of increasingly sophisticated and pervasive monitoring technologies, ultimately shaping the future landscape of digital civil liberties in America.