As shoppers moved through the bustling city center of Oxford on a crisp December day, they were met with a new and largely unseen presence in law enforcement: two specialized vans equipped with Live Facial Recognition (LFR) technology. Thames Valley Police officially deployed this system for the first time on December 22, 2025, marking a significant step in a national rollout of advanced surveillance tools designed to enhance public safety. This initiative, which aims to leverage artificial intelligence to identify wanted individuals and assist in ongoing investigations, has immediately become a focal point in the ongoing debate between security and privacy. The technology promises a more efficient and rapid response to crime, potentially locating dangerous offenders or vulnerable missing persons in a fraction of the time it would take traditional policing methods. However, its arrival also brings to the forefront critical questions about data protection, algorithmic bias, and the evolving relationship between the citizen and the state in an increasingly digital world.

The Mechanics of Modern Policing

The Watchlist System

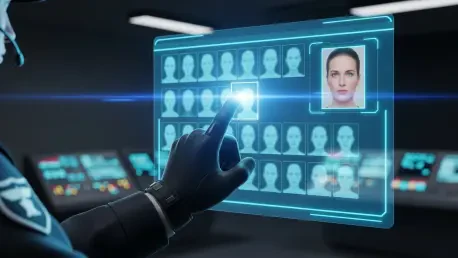

The operational effectiveness and privacy safeguards of the LFR system are fundamentally rooted in its use of a bespoke “watchlist” for each deployment. Contrary to common misconceptions of a massive, all-encompassing surveillance network, this technology operates on a highly targeted and temporary basis. Before a van is dispatched, a dedicated team of officers curates a specific list containing images solely of persons of interest relevant to that day’s mission. These individuals are typically wanted on court-issued warrants, have failed to appear for legal proceedings, or are otherwise sought in connection with specific criminal investigations. As the LFR cameras scan a public area, the system’s algorithm compares the faces it sees only against the images contained within this pre-approved, operation-specific watchlist. If a person is not on this list, a match is impossible. Critically, the biometric data of any non-matched individual is not stored; the digital template created for the comparison is automatically and permanently deleted within seconds, ensuring that the privacy of the general public is not compromised and no database of ordinary citizens is ever created.

The Human in the Loop Protocol

A central pillar of the Thames Valley Police’s LFR strategy is the non-negotiable “human-in-the-loop” protocol, a procedural safeguard designed to ensure that technology remains a tool to assist, rather than replace, human judgment. The system is not automated to trigger arrests or direct police action on its own. When the software identifies a potential match between a person in the crowd and an image on the watchlist, it generates an alert. This alert is not sent directly to officers on the street. Instead, it is first routed to a team of specially trained officers stationed inside the LFR van. These officers are responsible for conducting an immediate and thorough verification of the potential match, comparing the live image with the file photo to confirm the system’s accuracy. Only after a human officer has confidently verified the match are officers on the ground notified. At this point, the protocol calls for further human discretion. The patrol officers use their professional training and situational awareness to decide how to proceed, whether that involves engaging the individual, making an arrest, or, in cases involving a missing or vulnerable person, initiating a safeguarding intervention.

Balancing Crime Prevention with Civil Liberties

Official Endorsements and Safeguards

The introduction of LFR technology has received strong backing from key officials, including Matthew Barber, the Police and Crime Commissioner for Thames Valley. He has publicly framed the system as a necessary and powerful addition to the police’s toolkit, emphasizing its potential to significantly cut crime and expedite the capture of dangerous criminals. While endorsing the technology, Barber has also directly addressed the understandable concerns held by the public regarding surveillance and personal privacy. He assured that his office has worked closely with the police force to establish a framework of robust safeguards and clear policies governing the use of LFR. This framework is designed to ensure the technology is used proportionately and ethically. A core tenet of this approach is that the system is intended to target a specific and limited list of wanted individuals, not the general population. Barber has stressed that maintaining public consent and operating with complete transparency are vital for the program’s legitimacy, reiterating that the technology is designed to augment, not supplant, the professional judgment and discretion that remain the bedrock of modern policing.

A National Precedent and Its Legacy

The deployment in Thames Valley did not occur in a vacuum; it followed a series of similar initiatives by other police forces across the United Kingdom, which have collectively established a precedent for the technology’s effectiveness. These earlier rollouts have been credited with leading to hundreds of arrests for a wide range of serious offenses, including violent crimes such as rape, domestic abuse, and robbery, as well as offenses involving dangerous weapons. The positive results from these other regions provided a compelling case for the expansion of LFR as a valuable law enforcement asset. The implementation by Thames Valley Police, therefore, represented both a continuation of a national trend and a critical test of its public acceptance and operational efficacy. The careful balance struck between its crime-fighting potential and the stringent privacy protocols in place was seen as a model for future deployments. Ultimately, the long-term success of this technology was understood to depend not only on its technical performance but also on the force’s unwavering commitment to transparency and its ability to maintain the public’s trust.